Tracheostomy

Tracheostomy

David Ray Velez, MD

Table of Contents

Indications and Timing

Benefits (Compared to Prolonged Endotracheal Intubation)

- More Comfortable and Better Tolerated

- Decreased Work of Breathing

- Decreased Dead Space and Airway Resistance

- Improved Pulmonary Toilet, Oral Care, and Secretion Clearance

- Facilitates Liberation from the Ventilator

- Decreased Ventilatory Dependent Days

- Shorter Hospital Stay

- Shorter ICU Stay

Indications

- Will Require Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation > 7 Days

- Unable to Protect the Airway:

- Unable to Clear Secretions

- Severe TBI

- Severe Maxillofacial Injury

- Severe Neck/Vocal Cord Injury

- Complex Tracheal Repair

- Cervical Spinal Cord Injuries

- Ventilator Dependent Due to Frequent Trips to the OR

Contraindications

- Absolute Contraindications:

- Soft Tissue Infection at the Insertion Site

- Relative Contraindications:

- FiO2 > 60%

- PEEP > 12

- Hemodynamic Instability

- Anatomic or Vascular Abnormalities

- Midline Neck Mass

- Moderate-Severe Coagulopathy

- Morbid Obesity

- Percutaneous Approach is Contraindicated in Infants (Collapsible/Mobile Trachea)

Timing

- Definitions Vary

- Early: Performed within 2-14 Days

- Late: Performed Around 14-21 Days

- Benefits of Early Tracheostomy:

- Higher Likelihood of Ventilator Liberation

- Earlier Return to Walking, Talking, and Eating

- No Change In:

- Ventilator Associated Pneumonia (VAP)

- ICU Length of Stay

- Hospital Length of Stay

- Mortality

- Severe TBI and Cervical Spinal Cord Injuries May Particularly Benefit from Early Tracheostomy

Surgical Approach (Open vs Percutaneous)

- Percutaneous Tracheostomy

- Lower Risk of Surgical Site Infection

- Improved Scar Cosmesis

- Faster Procedure

- Lower Cost

- Similar Bleeding Risk, Decannulation Risk, and Mortality

Laryngotomia by Julius Casserius (1552-1616)

Materials and Types

Material

- Shiley (Coviden) – Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) Plastic

- The Most Commonly Used Material

- Bivona (Portex) – Silicone

- Softer and More Flexible

- Jackson – Metal

- Rarely Used in Modern Practice

Tracheostomy Material: Shiley (Left), Bivona (Middle), Jackson (Right)

Size

- In General, Use the Largest Size Possible for the Initial Placement

- Most Common Sizes:

- Adult Males: 8.0-8.5 mm

- Adult Females: 7.5-8.0 mm

Cuff

- Cuffed: Balloon at the End to Occlude the Surrounding Trachea

- Benefits:

- Allow Secretion Clearance

- Protects from Aspiration

- Allows More Effective PEEP

- Generally Preferred for the Initial Placement

- Cuff Pressure Should Be Maintained at 15-22 mmHg to Avoid Injury (Tracheal Capillary Perfusion Pressure is Normally 25-35 mmHg)

- Benefits:

- Uncuffed: Straight Tip with No Balloon at the End

- Allows Airway Clearance but No Protection from Aspiration

- Used More Commonly in the Long-Term Care and Ventilator Weaning

Tracheostomy Cuff: Cuffed (Left), Uncuffed (Right)

Fenestration

- Has an Additional Opening in the Posterior Tube, Above Any Cuff

- Also Requires a Fenestrated Inner Cannula

- Allows Airflow Past the Tube but Does Not Prevent Aspiration

- Used During the Weaning Process, Generally Not Used for the Initial Placement

Tracheostomy Fenestration: Fenestrated (Left), Non-Fenestrated (Right)

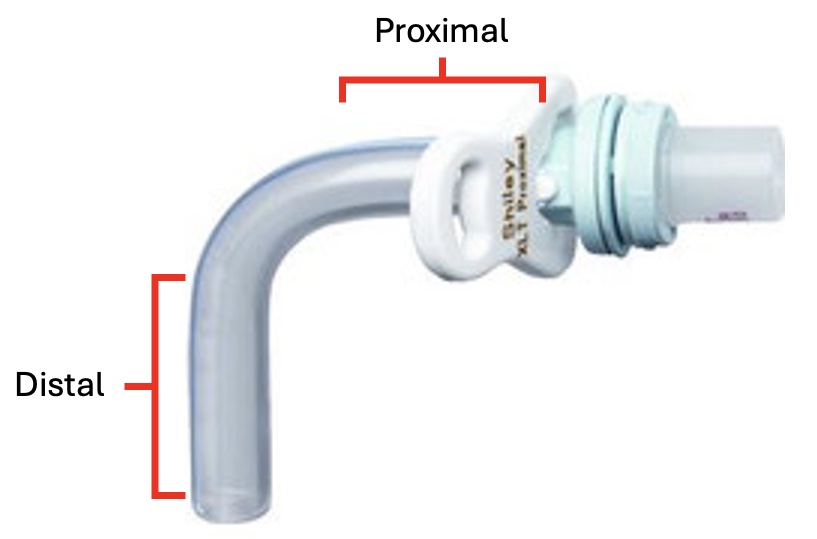

Length

- Standard

- XLT (Extended-Length Tube)

- XLTP – Extra Length Proximally (In-Neck Before the Radial Turn)

- For Swollen/Thick Neck Anatomy

- XLTD – Extra Length Distally (After the Radial Turn into the Trachea)

- For Long Tracheal Anatomy or Tracheal Stenosis

- XLTP – Extra Length Proximally (In-Neck Before the Radial Turn)

Tracheostomy Length

Complications

Accidental Decannulation/Dislodgement

Bleeding and Tracheoinnominate Fistula (TIF)

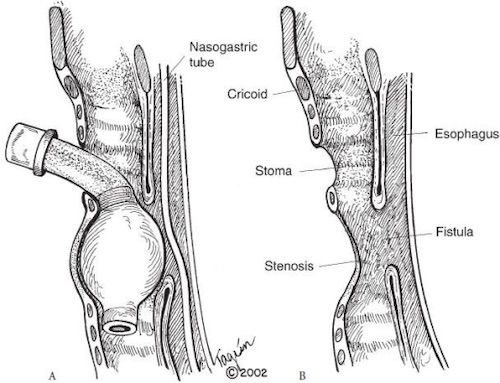

Tracheoesophageal Fistula (TEF)

- Risk Factors:

- High Cuff Pressure (#1)

- Concomitant Nasogastric (NG) Tube

- Excessive Motion

- Presentation:

- Ono’s Sign – Uncontrolled Coughing After Swallowing

- Respiratory Distress

- Recurrent Pneumonia

- Initial Management: Large Volume Cuff Endotracheal Tube Below the Fistula to Prevent Aspiration

- Definitive Treatment: Surgical Repair (Primary Repair vs Resection)

- May Consider Combined Tracheal and Esophageal Stenting if Not a Surgical Candidate

- Tracheal Stent Before Esophageal Stent – Esophageal Expansion May Compress the Trachea

- May Consider Combined Tracheal and Esophageal Stenting if Not a Surgical Candidate

Tracheoesophageal Fistula (TEF) 1

Tracheostomy Obstruction

- Causes:

- Mucous Plugging

- Clotted Blood

- Passage into A False Lumen (Paratracheal Soft Tissue)

- Tube Angulation

- Presentation:

- Acute Respiratory Deterioration

- Elevated Peak Airway Pressures

- Unable to Pass a Suction Catheter Through the Tracheostomy Tube

- Management:

- Can Initially Attempt Suctioning of the Tracheostomy Tube to Clear the Obstruction

- If Suctioning Fails: Exchange the Inner Cannula

- If Exchanging the Inner Cannula Fails or Cannot Be Removed:

- May Attempt Exchanging the Entire Tracheostomy Tube if the Tract is Mature

- Low Threshold to Secure the Airway by Endotracheal Intubation if in Respiratory Distress

Tracheal Stenosis

- The Most Common Late Complication

- Almost All Have Some Degree of Stenosis

- Only 3-12% Have Clinically Significant Stenosis

- Typically Seen at the Level of the Stoma

- Often Asymptomatic Until the Lumen is Reduced to < 5 mm (25-50% of Original Diameter)

- Presentation:

- Elevated Peak Airway Pressures if Infra-Stomal Stenosis

- Dyspnea, Stridor, and Respiratory Failure After Decannulation

- Grading:

- Grade I: ≤ 50%

- Grade II: 51-70%

- Grade III: 71-99%

- Grade IV: 100% (Complete Obstruction)

- Complexity:

- Simple:

- Length < 1 cm

- Only Involves the Mucosa

- Complex:

- Length ≥ 1 cm

- Involves the Cartilage

- Presence of Tracheomalacia

- Simple:

- Diagnosis: Bronchoscopy

- Treatment:

- Simple: Serial Bronchoscopic Dilations

- Possibly Bronchoscopic Resection or Laser Ablation

- Complex: Tracheal Resection (Up to 6 cm) and End-to-End Anastomosis

- Simple: Serial Bronchoscopic Dilations

References

- Paraschiv M. Tracheoesophageal fistula–a complication of prolonged tracheal intubation. J Med Life. 2014 Oct-Dec;7(4):516-21. (License: CC BY-2.0)