Esophagus Trauma

Esophagus Trauma

David Ray Velez, MD

Table of Contents

Background

The Majority are Due to Penetrating Trauma

Site

- Cervical Esophagus – Most Common

- Thoracic Esophagus – Less Common Due to Bony Protection

- Abdominal Esophagus – Least Common

Nearly All (98%) Have Other Associated Injuries

AAST Esophagus Injury Scale

- *See AAST

- Injury Scale is Under Copyright

Diagnosis

Signs/Symptoms

- Pain in the Neck, Chest, or Abdomen

- Dysphagia – Pain with Swallowing

- Nausea and Vomiting

- Hematemesis

- Dyspnea

- Cough

- Subcutaneous Emphysema

- Presentation is Generally Nonspecific

Delay in Diagnosis is Common and Requires a High Index of Suspicion

Diagnosis

- Start with a Water-Soluble Contrast Esophagram

- Can Pull NG Back to the Proximal Esophagus Before Contrast Instillation if Intubated

- If Negative but High-Suspicion of Injury: Repeat Esophagram with Dilute-Barium

- If Negative Again: Esophagoscopy

Specificity/Sensitivity

- Contrast Studies Alone Have High False-Negative Rates (25%)

- Esophagoscopy Has a High Negative Predictive Value (100%) but Low Positive Predictive Value (33%)

- A Negative Esophagram AND Esophagoscopy Have a Near 100% Specificity

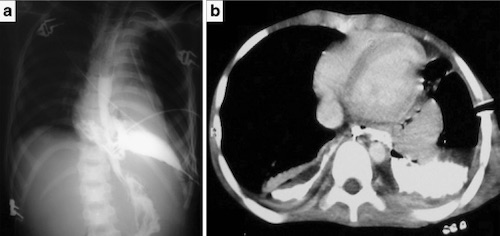

Traumatic Esophagus Perforation with Oral Contrast Extravasation 1

Treatment

The Primary Treatment is Surgical Repair Reinforced with Buttress and Drainage

Surgical Approach to the Esophagus

- Cervical Esophagus: Left Cervical Incision Along the Anterior Border of the Sternocleidomastoid (SCM) Muscle

- Thoracic Esophagus (Upper 2/3): Right Posterolateral Thoracotomy – Avoids the Aorta on the Left

- Thoracic Esophagus (Lower 1/3): Left Posterolateral Thoracotomy – The Aorta Transitions to the Right Distally

- May Be Able to Repair Through a Laparotomy Alone for Distal Injuries at the Esophagogastric Junction

Surgical Repair

- The First Step is to Extend the Myotomy to See the Full Length of Mucosal Injury

- The Muscular Defect is Almost Always Smaller than the Mucosal Defect

- Close the Defect in Two Layers without Tension

- Inner Absorbable Suture and Outer Permanent Suture

- The Submucosa is the Strength Layer – There is No Serosa in the Esophagus

- Transverse Repair is Preferred for Small Defects, but Large Injuries May Require Longitudinal Repair

- The Blood Supply is Longitudinal Through the Submucosa – Allows Full Mobilization

- Explore Circumferentially in Penetrating Injury to Verify No Back-Wall Injury

Buttress

- Esophageal Repairs Should Be Buttressed to Strengthen and Enhance Healing Given No Serosal Layer Which Increases the Risk of Postoperative Leak

- Neck: Strap Muscles or Sternocleidomastoid (SCM) Muscle

- Proximal Thorax: Intercostals or Rhomboid Muscle

- Muscle Flaps are Preferred – Less Friable and Provide More Bulky Coverage

- Other Less Desirable Options: Pericardium or Pleura

- Distal Thorax or Abdomen: Stomach (Nissen Fundoplication) or Diaphragm

Drainage

- Neck: Penrose or JP Drain

- Thoracic: Chest Tubes

- Abdomen: JP Drain

Damage Control Options

- Neck: Cervical Esophagostomy (Spit Fistula)

- Loop Esophagostomy If Able – Allows Easier One-Stage Closure as an End Esophagostomy Requires Complex Closure

- Thoracic: Large T-Tube (Creates a Controlled Fistula)

The Use of Endoluminal Esophageal Stents is Evolving but May Be an Appropriate Alternative for Damage Control

References

- Oikonomou A, Prassopoulos P. CT imaging of blunt chest trauma. Insights Imaging. 2011 Jun;2(3):281-295. (License: CC BY-4.0)